The City Less Lived

This article has been translated by John Clarke

Nothing said of Aglaura is true, and yet these accounts create a solid and compact image of a city, whereas the haphazard opinions which might be inferred from living there have less substance. This is the result: the city that they speak of has much of what is needed to exist, whereas the city that exists on its site, exists less.Cities and Names 1. Invisible cities by Italo Calvino

The cities that we live in today are comparable to the Aglaura that Calvino speaks of. In the shadow of the hotspots that are pointed out by guides, in adds, and the tourism board there lies a different reality in which the city exists less for the citizen than it does for the tourist. A facade of symbols that conceal the material conditions of the people who live in them. And this citizen/inhabitant does not only exist less here, but he is urged to assume the role of an extra in this tragicomedy that is the city – a picture perfect scene for the viewer: the tourist.

Two days ago, it was made public in local newspapers that the ‘Royal Tobacco Factory,’ now the rectory of the University of Seville, has become the latest historical space to be infiltrated by tourists. The holidaymakers in question came into the classrooms during lectures and did not leave before photographing the students. You can almost imagine them asking the students to smile for the picture! Let’s see, you at the back! Can you move over a little to the left? We can’t see you very well back there. Yeah, no, just a little more? Hold on I’m going to do another one for Instagram. You come into the light! Can you do that again only this time make a funny face as you’re doing it? Thanks.”

In the course of 2018, the tourism industry amassed 82.6 million tourists in Spain, surpassing the record of the previous year. In the shadows of the Ministry of Tourism’s celebrations and the companies that owed their success to this industry, a new and uncertain reality was taking shape: The precarious working nature of employees in the service sector. The rise of holiday rentals and the impact of this on the housing market. A spike in cheaper holiday destinations like Tunisia, Egypt and Turkey, or the Thomas Cook bankruptcy which resulted in the closure of up to five hundred hotels. To ignore the symptoms that indicate the fragility of this industry does not mean they will simply disappear. If anything this inaction will accentuate the inequality and precariousness of the conditions that citizens have to put up with.

There are three categories that people living in cities today fall into under the tourism industry: a consumer, an extra (they must become part of the backdrop of a stage set for the tourist), or a loser (a waste product of this aggressive and ruthless system). The diverse cultures of the city and the distinct heritages that colour it are taken out of context and commodified as tourist products devoid of meaning or history. Daily life is turned into a museum, and between the poorly parked electric scooters and every bus stop poster hailing the arrival of the new Triple Cheese Burger, public spaces become insufferable. Either you consume or you exist to serve the consumer. What does not belong to this version of the city is denied as false, cast out to the sidelines, and repressed. It is waste to be disposed of. Consequently, the tourism industry finds itself at the centre of an unsolvable paradox: In the process of placing value on heritage, its sites and cultures are consumed. They are pushed to the brink of an extinction whereby there are not significant features left to even distinguish them as a shell of what they were. In spite of all this, cities continue to pursue this course, sailing on the edge of all reason, just about existing, because as Jane Jacobs once said: “there is no logic that can be imposed on cities; the people are what make them, and it the people, then, and not the buildings which need to take precedence in our policy”.

We must ask what it means to be a city, to live in an urban space. Yes we can take lessons from history, but we must avoid the temptation to be overcome by nostalgia, or dwell on tales of identity. Cities have changed, and the ways they are narrated should include experiences of those who feel marginalised within them. They should feature those who do not normally feature in the stories of cultural tradition in the city. In another passage of Invisible Cities, it is said that there exist two types of city: “those that through years of change and transformation continue to adapt to the needs of the people, and those where these same desires and needs destroy or are destroyed by the city”.

Bringing these desires once again to light and rejecting the ones that have been imposed means being able to identify the desires of the citizen. It means crafting these desires from the same motives that brought humans into cohabitation in the first place. We must call on the law to define the city in the face of the unifying visions of technocrats and Blackstones, and demand change from those public institutions that submit before their overpowering inertia. Yet how can we hope to recover the story of the city if at the same time we leave its definition open to others who will muscle their way in and propose new meanings for it?

It is not surprising that we entrust the answer to this question to Henri LeFebvre.“Rights to the city” has been invoked as a slogan with almost magical properties to counter any process of dispossession within cities. On the other hand, this overuse of the term has resulted in a back and forth discussions over its meaning – a solution as impactful as using a finger to plug a hole in the hull of a ship. Fifty years on, we are still throwing ourselves at the parts of LeFebvre’s text that are left open to interpretation.

From a distance, the city appears to us as if unified under the gaze of those who hold power who, in giving half-effective solutions which favour political and economic interests, claim to be all knowing. LeFebvre proposes, however, that when we talk about unity we should think about it differently: He suggests the principle of a united city where wisdom and knowledge cooperate strategically with one another. Furthermore, he proposes to let recreation, understood in its broadest meaning and deepest sense, once again reclaim its centrality in our society. Sport is recreational, as is theatre. Activities for children and teenagers are equally far from negligible. Fairs and all sorts of communal games persist in the interspace of consumer-led society, hidden beneath the skin of this supposedly respectable society which claims to be structured and systematic, and which qualifies itself in technical terms.”

We want to take back the right to define the city in terms of a game. A game founded on/conjured from the ruins of logic where once upon a time cities may have stood. A game which can be shared “between the different pieces of the social set, which proclaims itself to have a supreme, important, and perhaps serious value that can be used to overcome the challenges that the city faces. A game that raises an imagination contrary to the one that already exists, an imagination that does not succumb to the temptation to avoid one’s problems – but to confront the conditions of our existence face to face. In “The city is ours” we will play seriously to imagine another form of living in our cities, to take back our right to live in them. And who knows? Maybe this spark will ignite the timbers of cities elsewhere.

—

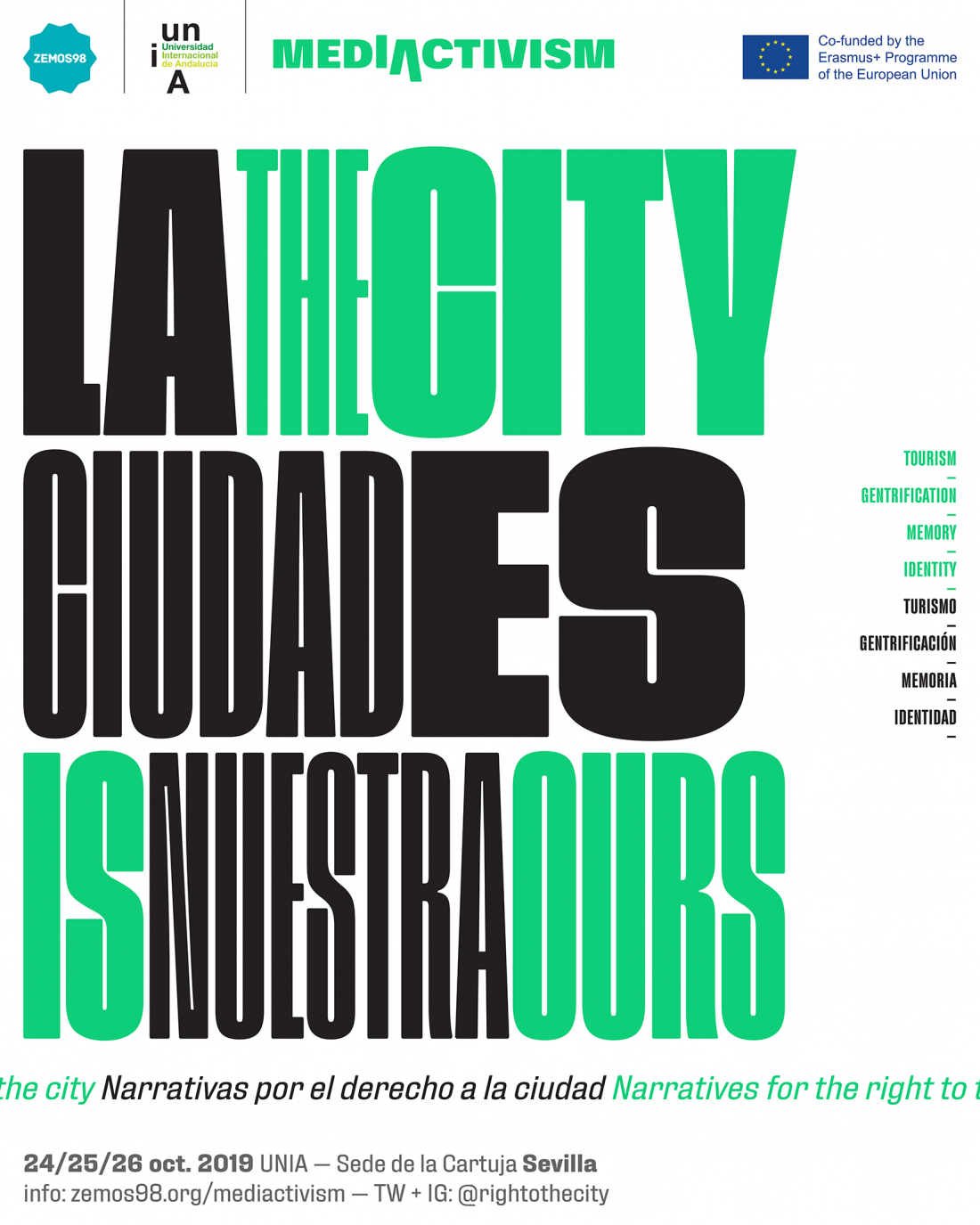

On October 24th, 25th and 26th we will be celebrating “The city is ours” in Seville, a meeting of 30 attendees from local, national and international destinations. This group will consist of individuals working in various fields, from memory, identity, folklore and tourism to art, audiovisuals, journalism and statistics. “The city is ours” is part of MediActivism, a project coordinated by the European Cultural Foundation. It is also backed by the International University of Andalucia.

No Comments